Commons:Derivative works

|

This project page in other languages:

Deutsch | English | Español | Suomi | Français | Galego | 日本語 | Português | Português do Brasil | Română | Русский | +/− |

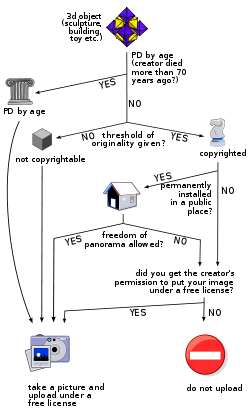

Many creative works are a derivative work of something, but in most cases, copyright can't be claimed on them because of varying factors. For photographs for example, exceptions include it not being a creative work, having utilitarian functions, freedom of panorama exemptions, and so on. However, in all other cases, only the copyright holder has the right to authorize derivative works. These include pictures of sculptures, action figures and other copyrighted works. The same principle applies to other works too, you can't make a movie version of a book you just read without the permission of the author either, because it would be a derivative work.

[edit] What is a derivative work?

Derivative works, according to the U.S. Copyright Act of 1976, Section 101, are defined as follows:

- "A 'derivative work' is a work based upon one or more pre-existing works, such as a translation, musical arrangement, dramatization, fictionalization, motion picture version, sound recording, art reproduction, abridgment, condensation, or any other form in which a work may be recast, transformed, or adapted. A work consisting of editorial revisions, annotations, elaborations, or other modifications, which, as a whole, represent an original work of authorship, is a 'derivative work'".

In short, all transfers of a creative, copyrightable work into a new medium count as derivative works. Also, all other modifications whose outcome is a new, creatively original work. Who may create such a derivative work? See U.S. Copyright Act of 1976, Section 106:

- "(T)he owner of copyright under this title has the exclusive rights to do and to authorize any of the following: (...) (2) to prepare derivative works based upon the copyrighted work".

As opposed to an exact copy or minor variation of a work (e.g. the same book with a different title), which does not create a new copyright, a derivative work creates a new copyright on all original aspects of the new version. Thus, for example, the creator of The Annotated Hobbit holds a copyright on all of the notes and commentary he wrote, but not on the original text of The Hobbit which is included in the book. The original copyright is still valid. The person who holds the copyright to, say, a Darth Vader action figure or a Picasso statue has the exclusive right to create derivative works. That includes photographs of the work, since (as court decisions put it) that is one aspect of the copyright holder's work that he or she might want to exploit commercially.

[edit] If I take a picture of an object with my own camera, I hold the copyright to the picture. Can't I license it any way I choose? Why do I have to worry about other copyright holders?

By taking a picture with a copyrighted cartoon character on a t-shirt as its main subject, for example, the photographer creates a new, copyrighted work (the photograph), but the rights of the cartoon character's creator still affect the resulting photograph. Such a photograph could not be published without the consent of both copyright holders: the photographer and the cartoonist.

It doesn't matter if a drawing of a copyrighted character's likeness is created entirely by the uploader without any other reference than the uploader's memory. A non-free copyrighted work simply cannot be rendered free without the consent of the copyright holder, not by photographing, drawing nor sculpting.

[edit] If I take a photograph of a kid who is holding a stuffed Winnie the Pooh toy, does Disney own the copyright in the photo since they own the Pooh design?

No. Disney does not hold the copyright on the photo. There are two different copyrights to be taken into account, that of the photographer (concerning the photo) and that of Disney (the toy). You have to keep those apart. Ask yourself: Can the photo be used as an illustration for "Winnie the Pooh"? Am I trying to get around restrictions for two-dimensional pictures of Pooh by using a photo of a toy? If so, then it is not allowed.

Be aware, though, that Disney's protection strategy both relies on author's right (artistic property) and trade mark (extended to protect a design). The actual legal analysis would be more subtle in that case.

While Disney does not hold a copyright on the photo, there may be an infrigement by virtue of copying via the photograph Disney's copyright Pooh. In fact, you may have created a derivative work without permission.

[edit] Isn't every product copyrighted by someone? What about cars? Or kitchen chairs? My computer case?

No. There are special provisions in copyright law to exempt utility articles to a wide degree from copyright protection:

The second part of the amendment states that

- "the design of a useful article [...] shall be considered a pictorial, graphic, or sculptural work only if, and only to the extent that, such design incorporates pictorial, graphic, or sculptural features that can be identified separately from, and are capable of existing independently of, the utilitarian aspects of the article."

A "useful article" is defined as "an article having an intrinsic utilitarian function that is not merely to portray the appearance of the article or to convey information." This part of the amendment is an adaptation of language added to the Copyright Office Regulations in the mid-1950's in an effort to implement the Supreme Court's decision in the Mazer case.

In adopting this amendatory language, the Committee is seeking to draw as clear a line as possible between copyrightable works of applied art and non-copyrighted works of industrial design. A two-dimensional painting, drawing, or graphic work is still capable of being identified as such when it is printed on or applied to utilitarian articles such as textile fabrics, wallpaper, containers, and the like. The same is true when a statue or carving is used to embellish an industrial product or, as in the Mazer case, is incorporated into a product without losing its ability to exist independently as a work of art. On the other hand, although the shape of an industrial product may be aesthetically satisfying and valuable, the Committee's intention is not to offer it copyright protection under the bill. Unless the shape of an automobile, airplane, ladies' dress, food processor, television set, or any other industrial product contains some element that, physically or conceptually, can be identified as separable from the utilitarian aspects of that article, the design would not be copyrighted under the bill. The test of separability and independence from "the utilitarian aspects of the article" does not depend upon the nature of the design—that is, even if the appearance of an article is determined by aesthetic (as opposed to functional) considerations, only elements, if any, which can be identified separately from the useful article as such are copyrightable. And, even if the three-dimensional design contains some such element (for example, a carving on the back of a chair or a floral relief design on silver flatware), copyright protection would extend only to that element, and would not cover the overall configuration of the utilitarian article as such.

- From Cornell University Law School notes on US Code 17 § 102

Sculptures, paintings and action figures do not have utilitarian aspects and are therefore generally copyrighted as works of fine art. On the other hand, ordinary alarm clocks, dinner plates, gaming consoles or other objects of daily use are usually not copyrightable.

It is possible for utilitarian objects to be copyrightable (for example, consider an alarm clock in the shape of a cartoon character), but there is no clear line between works which are copyrightable and objects which are not, and different jurisdictions use different criteria. For example, German law has a term called Schöpfungshöhe, which is the threshold of originality required for copyright protection. As in most jurisdictions, the level of originality required for copyright protection of works of applied art is higher. There is no legal definition for this threshold, so one must use common sense and existing case law.

Instead of copyright protection, utilitarian objects are generally protected by design patents, which, depending on jurisdiction, may limit commercial use of depictions. However, patents and copyright are separate areas of law, and works uploaded to Commons are only required to be free with respect to copyright. Patents are public knowledge, so publishing a depiction of a patented object on Commons cannot in itself constitute patent infringement. Therefore, patents of this kind are not a matter of concern for Commons.

Photos of people in costumes of copyrighted and/or trademarked characters, in general, are understood as lawful. [5]

[edit] Text

It is not allowed to copy text from non-free media like copyrighted books, articles or similar works. Information itself, however, is not copyrightable, and you are free to rewrite it in your own words. Quotations are allowed if they are limited in size and mention the source.

[edit] Maps

In the United States, many maps are in the public domain. The most common cases are:

- The map was created by the US government. The federal government is the greatest source of public domain maps in the United States. Federal agencies are creating maps all the time and works that US government employees create (as part of their jobs) are not protected by copyright.

- The map’s copyright has expired. All maps published in the United States before 1923 are in the public domain because their copyrights have expired.

- The map was published before 1989 without a copyright notice. Copyright notices used to be mandatory. If a work was published without a proper notice, it went into the public domain unless the copyright owner corrected the problem within a specific period of time. A valid copyright notice on a map had to consist of at least these 2 elements: the copyright symbol ©, the word "Copyright," or the abbreviation "Copr." and the name of the copyright owner. (Example: © Lenny Longitude). Maps published from January 1, 1978 through March 1, 1989 also had to include the publication year. (Maps published before 1978 didn't need to include the date).

- The map wasn’t eligible for copyright in the first place. Not all maps get get copyright protection in the United States. There are "originality" and "minimal creativity" requirements for copyright in the US. If the components of the map are "entirely obvious" the map will not be copyrightable. For example, an outline map of the state of Texas, or one of the US showing the state boundaries is not copyrightable. (Not creative.) Ditto maps that use standard cartographic conventions, like a survey map. (Not original.)[1]

Even for maps which are copyrighted, not all the contents are subjected to copyright. The problems arise from the tension between the principle that maps are protected and two other basic principles: namely, that copyright does not protect facts and that copyright does not protect systems. Traditional maps are pictorial representations of geographic and demographic facts organized to allow the user to readily understand and easily extract the factual information portrayed. The factual information, such as boundary lines and locations of landmarks, is supposedly unprotected. The organizing principle for presenting the information will often, if not always, be deemed an unprotected system or idea. Thus, many maps will apparently contain only unprotected elements.

The issue was the object of several court cases. The tension among traditional copyright principles as they apply to maps has been heightened by Feist Publications, Inc. v. Rural Telephone Service Company, Inc. The Feist decision follows standard copyright dogma to the conclusion: copyright protects only expression, not facts; the expression protected must be the product of intellectual creativity and not merely labor, time, or money invested; the protected elements of the resulting work are precisely those that reflect this intellectual creativity, and no more. This is the conclusion of a court of law on the issue. [2]

As a result of the court decisions, following parts of a map are in the public domain, and may be used freely:

- Place names. Those aren't copyrightable.

- Colors. For example, the colors representing area features on a topographic map, such as vegetation (green), water (blue), and densely built-up areas (gray or red). Colors aren't copyrightable, either.

- Symbols and map keys Can't be protected by copyright, even if the mapmaker invented truly original ones.

- Geographic or topographic features. Those are facts, and facts aren't copyrightable.

- Elements copied from other maps (say, from a public domain USGS map). Whatever new information the mapmaker added will be protected by copyright (the selection, arrangement of the info), but the elements that were copied (the elements of a USGS map used as a starting point, for example) will stay in the public domain.[1]

While the above applies to the United States, it is not clear if it is applicable to other countries. In the European Union Directive 96/9/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council of 11 March 1996 on the legal protection of databases has been approved. However, neither the directive, nor any of the national laws promulgated after its approval clearly specify that elements represented on maps qualify as databases.

In Germany a verdict of the court in München of November 9, 2005, stated that, according to the German Copyright Law [3] topographic maps are to be considered databases, as defined in art. 87 of the law and the information is protected according to the provisions regarding databases. This also refers to the length of the protection of databases which is significantly shorter than the protection of copyright. [4]

In any case, the copyright for databases according to the Directive is of fifteen years, implying that, regardless of the interpretation, the information on maps which could be interpreted as being database related expires in 15 years after the publication of the map.

[edit] I know that I can't upload photos of copyrighted art (like paintings and statues), but what about toys? Toys are not art!

Legally, most toys are art. It is the same thing whether you take a picture of a sculpture or a picture of Darth Vader. Both are copyrighted; in both cases, the copyright of the photograph does not void the original copyright, and in both cases you will need the permission of the original creator. You cannot upload pictures of a sculpture by Picasso, and you can't upload photographs of Mickey Mouse or Pokémon figures.

Numerous lawsuits have shown that Mickey Mouse or Asterix have to be treated as works of art, which means they are subject to copyright, while a common spoon or a table are not works of art. They can be copyrighted, perhaps, if they were given a very special form by a designer and presented as art (and not a spoon), but the ones you use at home are probably not. [5]

[edit] But Wikimedia Commons isn't commercial! And what about fair use?

Wikimedia Commons is not a commercial project, but the project scope requires that every single picture may be used commercially via free licenses. Every image or media file must be free of third-party copyrights.

Fair use is not allowed on Commons. "Fair use" is a difficult legal exception for pictures that are used in a certain limited context; it is not applicable on entire databases of copyrighted material.

[edit] But how can we illustrate topics like Star Wars or Pokémon without pictures?

Admittedly, it may be difficult or even impossible to illustrate such articles. However, the articles can still be written. Their lack of illustrations will not affect the vitality of Wikimedia's projects, and there are plenty of topics with opportunities to create illustrations which do not violate third-party copyrights.

Some Wikimedia projects allow non-free works (including derivatives of non-free works) to be uploaded locally under fair use provisions. The situations in which this is permitted are strictly limited. It is vital to consult the policies and guidelines of the project in question before attempting to invoke fair use claims.

[edit] I've never heard about this before! Is this some kind of creative interpretation?

Actually, no. Photographs of, say, modern art statues or paintings cannot be uploaded either, and people accept that. If we accept the legal standard that comic figures and action figures can be considered as art and thus are copyrighted, we are just applying the standard rule here.

[edit] Casebook

How does this policy concern the selection of images that are allowed on Wikimedia Commons?

- Comic figures and action figures: No photographs, drawings, paintings or any other copies/derivative works of these are allowed (as long as the original is not in the public domain). No pictures are allowed of items which are derivatives from copyrighted figures themselves, like dolls, action figures, t-shirts, printed bags, ashtrays etc.

- Paintings with frames: Paintings that are in the public domain are generally allowed (see Commons:Licensing). Frames are 3-dimensional objects, so the photo may be copyrighted. Remember: Always provide the original creator's name, birth and death date and the time of creation, if you can! If you do not know, give as much source information as possible (source link, place of publication etc.). Other volunteers must be able to verify the copyright status. Furthermore, the moral rights of the original creator—which include the right to be named as the author—are perpetual in some countries. In either case you need permission from the author to create a derivative work. Without such permission any art you create based on their work is legally considered an unlicensed copy owned by the original author (taking from another web site is not allowed without their permission).

- Cave paintings: Cave walls are usually not flat, but three-dimensional. The same goes for antique vases and other uneven or rough surfaces. This could mean that photographs of such media can be copyrighted, even if the cave painting is in the public domain. (We are looking for case studies here!) Old frescoes and other PD paintings on flat surfaces should be fine, as long as they are reproduced as two-dimensional artworks.

- Photographs of buildings and artworks in public spaces: Those are derivative works, but they may be OK, if the artwork is permanently installed (which means, it is there to stay, not to be removed after a certain time), and in some countries if you are on public ground while taking the picture. Check Commons:Freedom of panorama if your country has a liberal policy on this exception and learn more about freedom of panorama. (Note that in most countries, freedom of panorama does not cover two-dimensional artworks such as murals.)

- Full freedom of panorama: Australia, Austria, Bolivia, Brazil, People's Republic of China, Canada, Croatia, Colombia, Czech Republic, Ecuador, Germany, India, Ireland, Israel, Mexico, Netherlands, Peru, Poland, Singapore, Sweden, Slovakia, Spain, Switzerland, Turkey, United Kingdom

- Restricted or no freedom of panorama: Armenia*, Azerbaijan*, Belarus*, Belgium, Denmark**, Estonia*, Finland***, France, Georgia*, Hungary, Italy, Japan***, Kazakhstan*, Kyrgyzstan*, Latvia*, Lithuania*, Moldova*, Norway**, Paraguay*, Romania*, Russia*, Uzbekistan*, Ukraine, USA**

- * These countries limit their freedom of panorama to non-commercial uses of the image only.

- **These countries have freedom of panorama only for buildings, but not for sculptures or other works.

- ***These countries have full freedom of panorama only for buildings, whereas images of sculptures or other works may only be reproduced for non-commercial purposes.

- Replicas of artworks: Exact replicas of public domain works, like tourist souvenirs of the Venus de Milo, cannot attract any new copyright as exact replicas do not have the required originality. Hence, photographs of such items can be treated just like photographs of the artwork itself.

- Photographs of three-dimensional objects are always copyrighted, even if the object itself is in the public domain. If you did not take the photograph yourself, you need permission from the owner of the photographic copyright (unless of course the photograph itself is in the public domain).

- Images of characters/objects/scenes in books are subject to any copyright on the book itself. You cannot freely create and distribute a drawing of Albus Dumbledore any more than you could distribute your own Harry Potter movie. In either case you need permission from the author to create a derivative work. Without such permission any art you create based on their work is legally considered an unlicensed copy owned by the original author.

- Fan art : See Commons:Fan art

[edit] See also

- Commons:Collages - combination of multiple images arranged in a single image

[edit] References

- ↑ a b [1] Public Domain Sherpa

- ↑ Dennis S. Karjala - Copyright in electronic maps - Jurimetrics Vol. 35 (1995) pp.305-415

- ↑ [2] Gesetz über Urheberrecht und verwandte Schutzrechte (Urheberrechtsgesetz)

- ↑ [3] Landgericht München I - Datenbankschutz für topografische Landkarten

- ↑ [4] Public Domain Sherpa

[edit] External links

- Case studies

- http://www.ivanhoffman.com/beanie.html (Citing a court case in which photographs of Beanie Baby dolls are treated as derivative works)

- http://www.benedict.com/Visual/batman/batman.aspx (Citing a court case in which Warner Bros was accused of copyright infringement for filming a statue inside a building)

- Other useful sites

- http://www.chillingeffects.org/derivative/faq.cgi#QID385

- http://docs.law.gwu.edu/facweb/claw/lhooq0.htm

- http://www.copyright.gov/circs/circ14.html#derivative/

- http://ipmall.info/hosted_resources/CopyrightCompendium/chapter_0500.asp (What's copyrightable and what's not?)

- Australian Copyright Council's Online Information Centre has many downloadable guides covering aspects of copyright.

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||